Weber in J. Brom. Soc. 32(6): 245. 1982

In Flora Neotropica L. B. Smith places T. neglecta Pereira as a synonym for T. tenuifolia var. surinamensis (but with a question mark). The specimens which I examined (WEB 324 and living material, leg. R. Ehlers, Jul. 1981, Cabo Frio) regularly show, however, only a few fused sepals and accordingly do not belong to the polymorphic T. tenuifolia, whose posterior sepals are always fused. T. neglecta Pereira is more probably related to T. stricta Solander ex Ker-Gawler 1813, but distinct from it. (The original description of T. stricta Sol. is designated with G. According to information from Dr. Vickery, British Museum, that is the sign of Ker-Gawler).

Two Locally Endemic Brazilian Tillandsias by Elton M.C. Leme in J. Brom. Soc. 37: 217-9. 1987

In the coast, contrasting with the blue-green ocean, there are solid walls of stony hills up to 400 meters high. Here and there, they break the monotony of the scenery and block the way to the sandy plains. The vegetation is typical of the sand dunes. Dense and continuous, it varies between the shrubby and the arboreous. At points it is so dense that it nearly eliminates bromeliads. Billbergia iridifolia (Nees & Martius) Lindley, an epiphyte growing just above the ground is the only exception. But where the sunlight pierces the lower stratum of the vegetation, large formations of Cryptanthus spp., Nidularium atalaiaensis Pereira & Leme, as well as other species, can be seen growing on the ground or on rocks. Sometimes, because they are so big, specimens of Bromelia antiacantha Bertoloni and Streptocalyx floribundus (Martius ex Schultes filius) Mez can be seen growing as terrestrials and surpassing the height of the woody vegetation.

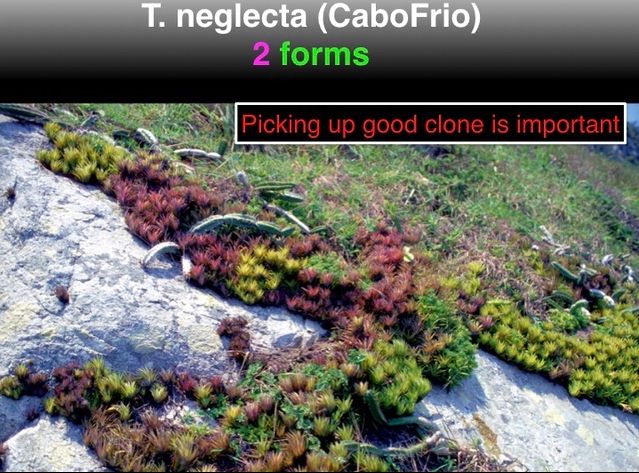

On the granitic walls where most species of plant life cannot grow, cactus columns appear in the middle of thickets of Neoregelia cruenta (R. Graham) L.B. Smith (Fig. 8), Quesnelia quesneliana (Brongniart) L.B. Smith, Billbergia tweedieana Baker, and conspicuous formations of Tillandsia neglecta E. Pereira. The sun and wind are merciless.

There are rocky islands near the shore cut off from the mainland by the wave action of centuries. These islands are inhabited by the same animal and plant species found on the mainland. We have one particular island in mind. It is the only place, to our knowledge, where Tillandsia gardneri Lindley var. rupicola E. Pereira grows. It is Cabo Island, also known as Farol Island.

All of this scenery was created by the forces of nature in the vicinity of Arraial de Cabo, State of Rio de Janeiro, about 160 km east of the city of Rio de Janeiro by highway.

The village of Arraial de Cabo, formerly a district of the County of Cabo Frio, was recently given a higher status, thus becoming politically and administratively autonomous. In spite of the destructive actions of men begun in this region in the 16th century, the natural areas of this new county are still reasonably well kept. The largest one is the Massambaba, a narrow sand barrier between the sea and the Araruama Lagoon. This sandy plain with its rolling lands has sparse vegetation, low growing and adapted to these dry and hot conditions. The plants very often form islands surrounded by winding rows of sand (Fig. 9). The edges of the islands are the habitat of terrestrial sun-lovers such as Aechmea pineliana (Brongniart ex Planchon) Baker, Neoregelia cruenta, N. eltonia W. Weber, Portea petropolitana (Wawra) Mez and Vriesea neoglutinosa Mez.

Among the epiphytes are Aechmea lingulata (Linnaeus) Baker, Billbergia euphemiae E. Morren, B. zebrina (Herbert) Lindley, and Tillandsia gardneri Lindley var. gardneri. Where the soil is deeper the vegetation grows eight to 12 meters high encouraging the growth of other bromeliad species as for example Aechmea sphaerocephala Baker, Billbergia pyramidalis (Sims) Lindley var. lutea Leme & Weber, Vriesea procera (Martius ex Schultes f.) var. rubra L. B. Smith.

As a result of the comparative preservation of these areas and also as a result of a survey made in this region, I positively established the existence of 36 bromeliad species, of which 30% are endemic. Because of their peculiarities, two of the species attracted our attention. They are Tillandsia neglecta and T. gardneri var. rupicola.

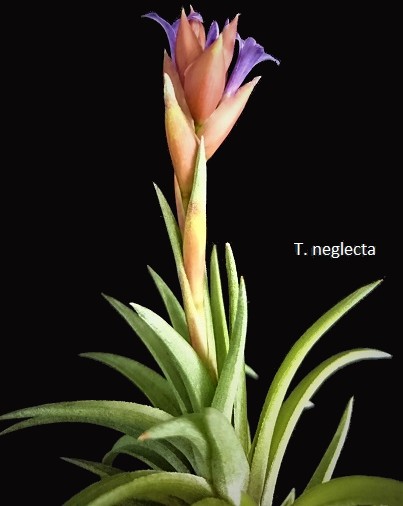

Tillandsia neglecta (Fig. 10) described in 1971 on the basis of material collected by Dimitri Sucre, has caused specialists to disagree as to its validity. In the highly respected opinion of Dr. L.B. Smith this species might be considered a synonym of T. tenuifolia var. surinamensis (Mez) L.B. Smith. On the other hand, Wilhelm Weber's views are that T. neglecta is more related to T. stricta Solander ex Ker-Gawler, but distinct from it. In fact, Edmundo Pereira in describing the species considered it taxonomically more closely related to T. stricta, pointing out as differences between them the distinct caulescent habit of T. neglecta, the degree of concretion of its posterior sepals, and the shape of the leaves. We consider the species valid, that in its habitat it bears great resemblance to T. araujei Mez, although sturdier. As to the floral elements it is really nearer to T. stricta.

Growing on the rocky cliffs of the mainland as well as on islands, T. neglecta develops in thick populations. The coloring of its leaves, which varies from yellowish green to bronze, is striking. Atalaia Hill and Cabo Island, separated by a few hundred meters, nowadays contain larger concentrations of the species. The island may be considered a nature preserve. Besides its isolation, the island has had the benefit of protection by the Brazilian Navy which does not allow unauthorized visitors. It has all kinds of sand bank vegetation from the shrubby to the arboreous. Its height is up to 406 meters and the forest that grows above the 200 meter line resembles the flanks of the Atlantic forest because of the marked humidity. It is interesting to note that of 20 different species of bromeliad growing on the island at least two of them, T. geminiflora Brongniart and Vriesea gigantea Gaudichaud, are typical of the Atlantic forest and have never been found growing in similar sandy locations on the mainland. The other species are mostly represented by members of the subfamily Bromelioideae and also grow on the mainland, in sand dunes nearby, without any noteworthy morphological variation between island and mainland populations. The only exception is T. gardneri var. rupicola which appears only on the rocky walls on the bare side of Cabo Island.

While the typical T. gardneri is chiefly of epiphytical habit with individuals more or less sparsely distributed within its ample area of occurrence, var. rupicula, as far as is known, entirely covers the rocky slopes (Fig. 11) with extremely dense populations, resembling the style of T. neglecta. It also grows side by side with T. neglecta.

Edmundo Pereira described this variety in 1981 on the basis of a specimen collected by Luiz Correia de Araujo. He found among the characteristics that distinguish the var. rupicola from the typical variety the unusual habit, the shape of the plant with strongly secund leaves, the branches of the inflorescence more spread out, and the coloring of the petals. At first, only the white color of the petals was known-seemingly the predominant pattern of the variety. Later, it was found that the petals may be of a bluish color, which may be a result of a process of hybridization with T. neglecta.

There is an interesting question about the origin of the species; the way in which it could have developed until its present condition. At first, we believed that because of its comparative isolation, the population of the island had adjusted to local conditions becoming different from the typical T. gardneri on the mainland. But if we consider that of all the bromeliological flora of the island only this variety is an exclusive element of the place, and that there are also species originating from the somewhat distant Atlantic forest, it is also a reasonable admission that the var. rupicola could have had a population much more widely distributed in the past. It might have grown on the rocky cliffs emerging from Atlantic heights like the Orgao Mountains. Because of some unknown factors, they have disappeared from these surroundings leading us to the conclusion that the population of Cabo Island could be relics, witnesses of old periods of vegetation. It is obvious that more studies and observations will be necessary in order to understand the mysteries enveloping T. gardneri var. rupicola.

Either of these varieties or the T. neglecta can be cultivated with comparative ease on pieces of tree branches. They will bloom every year without any special care.

In January 1987, in one of the last acts of the State government, it was directed that the sand banks of Arraial de Cabo would be considered an area of permanent preservation or of limited use. There is, however, concern that the new government may not continue to support the idea of preservation. In spite of these worries, there is a good probability that Cabo Island, because of its comparative isolation, will continue to be preserved over the years, a guarantee of survival of the flora and fauna of the region for present and future studies, or merely for the delight of those who love nature.