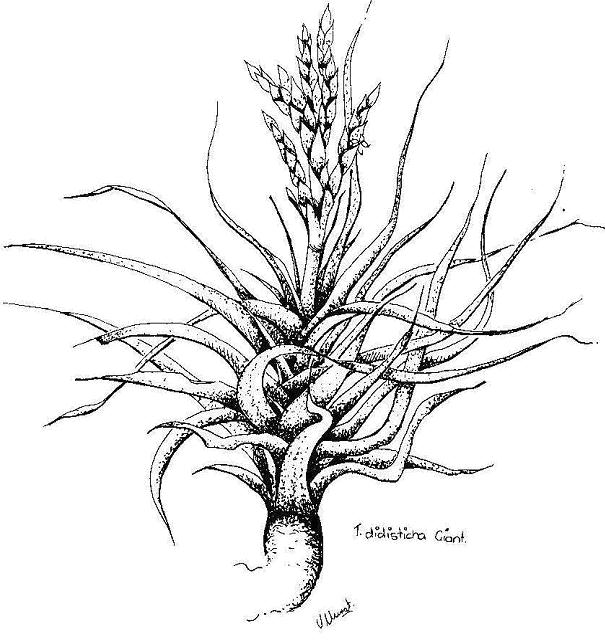

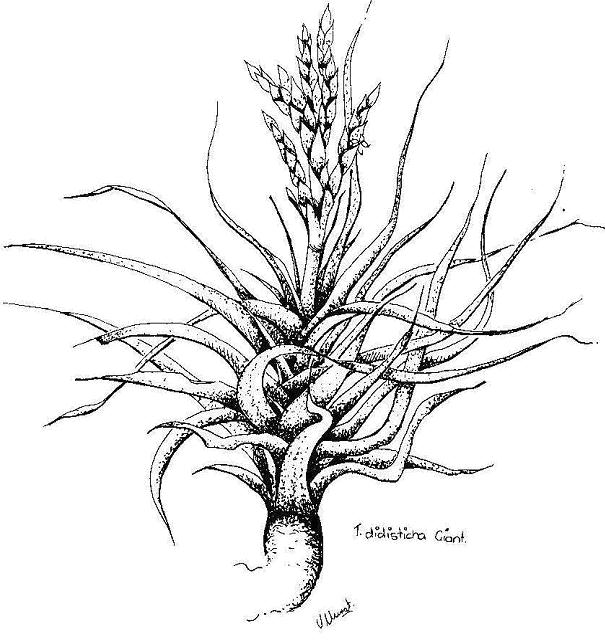

Tillandsia didisticha Giant

October 2005

MONTHLY RAFFLE PRIZE ROSTER:

October . . . . Alan/Graham

November. . . . John Flemming/Dawn/Rosetta

February. . . . Ailsa/Vonda/Neville

DULCIE DOONAN MEMORIAL TROPHY:

We would like to say a huge “Thank You” to Sharyn [Baraldi] who has donated the perpetual trophy which will be presented each year to the winner in the “Creative Section” of our Show whose entry most embodies Dulcie’s love of Cryptanthus and includes this genus in their arrangement.

SHOW RAFFLE PRIZES:

The raffle was very successful, thanks to the very generous donations made by four of our members. We would like to say a very heartfelt “Thank You” to David for another of his wonderful carved heads; to Keith for his bromeliad-filled log; to Sylvia and Ted for the lovely basket of bromeliads; and to Pat Alton for the two beautiful knitted lace coat hangers.

GARDEN VISITS:

The garden visits we had planned for November have, unfortunately, had to be postponed until a later date.

BUS TRIP:

Beth and Pat are organising a bus trip for late February to take in two bromeliad nurseries, plus perhaps another one or two nurseries, around the Galston/Dural area. Tentatively, we have set the date for Saturday, February 25. 2006. at around the cost of $25. More details at our November meeting.

CHRISTMAS PARTY:

Once again we will have the use of Leanne and Ken’s beautiful garden as the venue for our Christmas party this year. We will have the usual 11.00 am start to give us the chance to enjoy this lovely location, and for those new to our Society, the address is: 31 Redall Parade, LAKE SOUTH [make an immediate left after the bridge when heading south through Windang]--phone: 02 4295 6898. Extra details will be worked out at our November meeting, but, basically, it will be pretty much the same as past years: bring a plate and a small gift for sharing.

LIBRARY REMINDERS:

· Books, journals, videos, etc. are to be taken out on a one-month basis only.

· A reminder that we would like to have library items returned at or before our December meeting so that Pat can have an opportunity during the break to reorganise things before our February meeting.

GARDENS ON THE INTERNET:

Moyna Prince, of the Bromeliad Society of South Florida has included a little article on Wally Berg and his garden in the September 2005 issue of her newsletter, The BromeliAdvisory. Of course this prompted me to go to the fcbs site where there are pictures of this beautiful garden—as it used to be!—but there are also pictures of other gardens, including Moyna and Ed Prince’s own garden, Herb Plever’s incredible collection which he grows in his 8th floor apartment in New York City, as well as photographs of bromeliads in habitat—travels with Wally Berg and friends to Ecuador, Guatemala to El Salvador to Belize, and Panama. The FCBS web site is at: www.fcbs.org and to find these other gardens, on the menu on the left, click on Photo Index, then go to Programs, where you will find these and other interesting items listed.

A REPORT ON OUR THIRTEENTH ANNUAL SHOW, HELD AT THE UNITING CHURCH HALL, CORRIMAL, SEPTEMBER 10-11, 2005:

Graham and I would like to thank all of our members who worked so hard over the three days to make our Show such a success. Years ago I was cautioned not to mention names as there would surely be someone left out, and so this time I’ll follow that advice. However, we do want to let everyone know how very much we appreciated all of the effort put in in so many different areas.

Phillip told me that many people had come up to him to let him know how much they had enjoyed our Show—especially the display—and when I spoke with Colin Williams of the Uniting Church about booking again for next year, he told me about how much they enjoyed having us there.

We had 114 entries from 17 members in the competitive section of the Show, which was very good. But perhaps we might be able to coax some more of our newer members to compete in the Novice Section next year?!

Below is a copy of a letter from Debbie Hurst who was one of our judges, and who has written the letter, hoping that it may help members better understand what a judge is looking for in competition.

PS: Don’t forget the other Shows that are coming up this month:

· October 8-9 - Bromeliad Society of Australia’s Spring Show at Burwood RSL

· October 29-30 - Bromeliad Society of New South Wales’ Spring Show, CONCORD

My name is Debbie Hurst and I am a member of several societies, including this one. I am currently attending judging school which has nearly ended and as a student judge was asked to help judge your spring show. John Noonan is an accredited judge and he was very helpful in guiding me through the plants.

Overall the entries were quite good, but a few plants had leaves or old mother plants that could have been removed, which could have gained the owner a prize.

The Novice Section was not very well represented, with only one plant in a few sections, or none at all.

In Novice Neoregelia, one plant had to be excluded from the competition because the class called for a single specimen only and the pot contained 2 plants. Please read your schedules as you are missing an opportunity to gain a placing.

I was pleased with the decorative section in the show. Your Society has very talented members. The entry decorated with frogs was delightful and a worthy winner. Congratulations to all the winners.

My daughter Carolyn and I wish to thank members for their hospitality, as we had the best chicken sandwich that we have tasted for a long while. I hope that your show was a success because the effort you put into the display was excellent. Keep up the good work!

Thank you for an enjoyable morning.

| 1st | Nina and Jarka Rehak | Aechmea fulgens (variegated) |

| 2nd | Ted Clare | Aechmea recurvata hybrid |

| 3rd | Graham Bevan | Aechmea gamosepala var. nivea |

| 1st | Nina and Jarka Rehak | Billbergia Hallelujah |

| 2nd | Graham Bevan | Billbergia amoena var. minor |

| 1st | Nina and Jarka Rehak | Neoregelia Inferno |

| 2nd | Nina and Jarka Rehak | Neoregelia Mon Petite |

| 3rd | Eileen Killingley | Neoregelia Rosy Morn |

| 1st | Ailsa McDonald | Neoregelia Small World |

| 2nd | Ailsa McDonald | Neoregelia Small World |

| 3rd | Ailsa McDonald | Neoregelia One and Only |

| 1st | Nina and Jarka Rehak | Tillandsia tectorum |

| 2nd | Catherine Wainwright | Tillandsia tenuifolia |

| 3rd | Catherine Wainwright | Tillandsia ionantha |

| 1st | Nina and Jarka Rehak | Vriesea Sunrise |

| 2nd | Ted Clare | Vriesea fosteriana |

| 3rd | Suzanne Burrows | Vriesea guttata |

| 1st | Ailsa McDonald | XNeophytum Galactic Warrior |

| 2nd | Russell Dixon | Hechtia species |

| 3rd | Nina and Jarka Rehak | Cryptanthus Marion Oppenheimer |

| 1st | Carolyn and David Buxton | XVriesea corcovadensis |

| 2nd | Eileen Killingley | Aechmea Mary Brett x distichantha |

| 3rd | Graham Bevan | Neoregelia lilliputiana |

| 1st | Suzanne Burrows | Aechmea recurvata var. recurvata |

| 1st | Suzanne Burrows | Neoregelia Gespacho |

| 2nd | Dawn Climent | Neoregelia Stormy Forest |

| 3rd | Dawn Climent | Neoregelia Bob and Grace |

| 1st | Suzanne Burrows | Tillandsia bulbosa |

| 2nd | Suzanne Burrows | Tillandsia schiedeana |

| 3rd | Suzanne Burrows | Tillandsia tricolor |

| 1st | Suzanne Burrows | Orthophytum Warren Loose |

| 1st | John Fleming | Tillandsia Houston - a showy clump on tall root |

| 2nd | Ted Clare | Tillandsia tree - a collection mounted on branch |

| 3rd | Carolyn and David Buxton | Tillandsia filifolia - 3 dainty plants mounted on wood |

| 1st | Carolyn and David Buxton | Neoregelia Fireball x |

| 2nd | Ted Clare | Neoregelia - on driftwood |

| 3rd | Graham Bevan | Neoregelias - mounted |

| 1st | Graham Bevan | Pond Garden |

| 2nd | Graham Bevan | Cryptanthus Dish Garden |

| 1st | Sharyn Baraldi | Large Pot Garden - Frogs’ Hollow |

| 2nd | Patricia Alton | Bromeliad Garden |

| 3rd | Dawn Climent | Cryptanthus in Large Shallow Saucer |

| 1st | Elizabeth Bevan | Arrangement entitled ‘Anarosa’ |

| 2nd | Elizabeth Bevan | ‘Seaside Reflections’ |

| 3rd | Elizabeth Bevan | ‘Pre-Wedding Afternoon Tea’ |

| 2001 | 9th Show | 84 entries | 14 competitors |

| 2002 | 10th Show | 110 entries | 16 competitors |

| 2003 | 11th Show | 147 entries | 18 competitors |

| 2004 | 12th Show | 102 entries | 21 competitors |

| 2005 | 13th Show | 114 entries | 17 competitors |

| Oct. 8 - 9 | BROMELIAD SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA – SPRING SHOW – BURWOOD RSL, Cnr. Shaftesbury Road and Clifton Avenue |

| Oct 14 - 17 | BROMELIADS XIII CONFERENCE, BRISBANE – For information on this event please see Eileen, or visit the Website at www.bsq.org.au |

| Oct 20 - 23 | BERRY GARDENS FESTIVAL: Open 10.00 am to 4.00 pm daily |

| Oct 29 - 30 | BROMELIAD SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES - SPRING SHOW - Senior Citizens Centre, 9-11 Wellbank Street (Cnr Bent St), CONCORD |

| Nov. 5 - 6 | HUNTER DISTRICT BROMELIAD SOCIETY ANNUAL SHOW (Venue to be advised.) |

| Nov. 5 - 6 | Bromeliad Society of Queensland’s BROMELIAD BONANZA SPRING SHOW – MT COOT-THA (BRISBANE) AUDITORIUM – Talks/Displays |

| 2006 | |

| April 7 - 20 | Bromeliad Society of New South Wales – Display and Competition at Royal Easter Show - Homebush |

| April 29 - 30 | Bromeliad Society of New South Wales - Autumn Show - Concord |

MEETINGS:

| 1st | Ted Clare | Billbergia sanderiana |

| 2nd | Alan Kirkby | Guzmania Decora |

| 3rd | Alan Kirkby | Guzmania Amethyst Girl |

| 1st | Sue Burrows | Neoregelia Mottles |

| 2nd | Sue Burrows | Neoregelia Sugar and Spice |

| 1st | Graham Bevan | Tillandsia punctulata |

| 2nd | Graham Bevan | Tillandsia recurvifolia var. subsecundifolia (Lovely, with 3 inflorescences!) |

| 3rd | Sue Burrows | Tillandsia stricta hybrid |

| 1st | Ted Clare | Neoregelia carolineae x concentrica |

| 2nd | Rena Wainwright | Vriesea hybrid |

| 2nd | Alan Kirkby | Neoregelia Blast |

| 3rd | Alan Kirkby | Neoregelia Grand Fantastic |

| 3rd | Graham Bevan | Neoregelia pauciflora |

| 3rd | Graham Bevan | Neoregelia Fireball hybrid |

| 1st | Sue Burrows | Neoregelia spectabilis |

| 2nd | Sue Burrows | Billbergia nutans |

| 1st | Ted Clare | Tillandsia bulbosa |

| 2nd | Rena Wainwright | Tillandsia tenuifolia var. surinamensis (Black form) |

| 3rd | Ted Clare | Tillandsia latifolia v. divaricata |

| 3rd | Sue Burrows | Tillandsia bulbosa + cacticola(?) mounted on a very pretty piece of driftwood. |

| 1st | Ted Clare | Aechmea recurvata |

| 2nd | Nina Rehak | Aechmea fulgens (variegated) |

| 3rd | Alan Kirkby | Neoregelia Predatress |

| 1st | Rhonda Patterson | Aechmea caudata |

| 2nd | Rhonda Patterson | Aechmea recurvata |

| 2nd | Dawn Climent | Vriesea platynema |

| 3rd | Dawn Climent | Neoregelia Gespacho |

| 1st | Rena Wainwright | Tillandsia ionantha (A most magnificent clump on wood) |

| 2nd | Ted Clare | Tillandsia gardneri |

| 3rd | Sue Burrows | Tillandsia bulbosa |

1. Billbergia nutans ‘Mini Form’: Pat (Alton) brought in a pot of this lovely little plant, with around 20 bright pink inflorescences, to our September meeting. Tropiflora lists it as “… a strange little plant that was collected in Paraguay by Carlyle A. Luer of orchid fame. Variable, it usually has stiff, succulent leaves with stiff spines in a miniature, stoloniferous, spreading, few-leaved rosette. Sometimes it makes a tubular rosette, more typical of the species.” Pat’s plant fitted this latter description.

2. Neoregelia ‘Gespacho’: The Bromeliad Cultivar Registry lists this as a cultivar of unknown parentage made by D. Bryant (?) around 1991, but says that it may be N. chlorosticta(?) x ‘Fireball’(?). It is a beautiful multi-coloured Neoregelia with fairly wide red leaves which are blotched, banded and speckled with yellow-green, forming a medium-sized rosette to 12 inches or so. Yellow-white areas often form wide concentric bands when grown optimally.

3. Neoregelia spectabilis:: Plants by this name have been in cultivation since popularized by Mulford Foster in the 1950s. However, the species has almost long since been hybridized out of existence in cultivation. It is an upright grower with bronzy foliage, red tips and silvery banding below. Because of its bright coloured tips, it is sometimes known as the “fingernail plant”.

(Tropiflora Cargo Report http://www.tropiflora.com/creport/cr13-1/p3.html)

I live in Brisbane. While the air temperature sometimes drops to 4C for several nights in succession during winter, I have not experienced any frost. During summer the maximum temperature can be in the range of 35C to 38C for several days at a time. Occasionally such temperatures are combined with low relative humidity—e.g., 20% to 30%--although, thankfully, this combination is rare. This is fortunate as these conditions, that is high temperatures and low humidity, can be very damaging to many bromeliads. Winters are relatively dry, while summers are normally quite wet.

When designing a shadehouse, it is worth considering Bromeliads’ preferred growing conditions. I mainly grow the epiphytic ones such as Aechmeas, Canistropsis (Nidulariums), Guzmanias, Neoregelias, Tillandsias and Vrieseas.

These plants like:

· Lots of air movement around them throughout the year;

· Good light (but not full sun) from all directions; and

· Their potting mixture to become fairly dry between waterings.

The shadehouse I built is about 6 metres so, while it isn’t anywhere near as large as those used by commercial growers, it is bigger than many of the “kit-type” shadehouses.

The optimal shadehouse location is one where sunlight falls on the structure throughout the day. This achieves at least 9 hours sunlight in winter, and 12 or more hours in summer.

Unfortunately, I cannot achieve this outcome. In my case, the shadehouse receives about 5 hours of sunlight in winter and around 10 hours in summer. It receives most of the morning sun and the afternoon sun until about 2pm (in winter) and 3.30pm in summer. So, the challenge for me is to obtain the best use of the winter sun, while not “burning” plants in either winter or summer.

The frame for the shadehouse was built out of 20mm galvanized pipe. I could have used hardwood timber, but as I had some spare pipe, I used that. If you are using hardwood, consider painting it. This will protect the bromeliads from being damaged by any copper salts which may “leach out” from the hardwood (this may occur if the timber is treated with a copper-based preservative which is usually the case). It will also increase the amount of light reflected onto the plants from within the shade house.

I used a high gloss acrylic white paint on most of the shadehouse’s wooden surfaces—e.g., a wall. It is certainly noticeably lighter inside than another shade house in a similar location where this was not done. Gerry Stansfield from New Zealand told me that using a high gloss acrylic paint will also make it easier to remove any algae, which may grow on the painted surface. You don’t have to confine yourself to painting only wooden surfaces. Doug Upton has painted part of a concrete wall inside his shadehouse.

While I was able to construct my shadehouse to a height of only 2.4 metres, build it higher if you can as air circulation seems to improve with increasing height. Some commercial shadehouses are over 6 metres high. Also, the higher the roof the more opportunity you have to hang plants above the benches, and thus fit more plants into the shadehouse.

Incorporate existing structures—e.g., walls—into the shadehouse wherever you can to help keep the cost down. One of my shade house’s walls is an existing fence built from wooden palings. This works well in summer, and in winter I cover the fence’s exterior (to the shade house) surface with reinforced plastic film to keep out the strong, cold, dry, westerly winds.

To cover the shadehouse I used knitted shade cloth. The eastern “wall” is 50% “shade”, as is the southern wall. (In my location, the southern wall is in a very protected position.) The northern wall is part of another shadehouse, while the western wall is the paling fence. The roof is 50% shade, which provides the right amount of shade for many bromeliads—e.g., most Aechmeas, Neoregelias, Tillandsias and Vrieseas during winter, but will be inadequate for most of them during the hottest months of the year (basically, mid- November to the end of March). During this period, more shade will be obtained by placing an extra piece of 50% to 75% shade cloth underneath the shade cloth forming the roof. (As a matter of interest, the percentage figure quoted for various types of shade cloth is the amount of ultraviolet light they exclude, not the amount of shade they give. A shade cloth with a 50% rating will let in more than 50% of the sun’s rays, on most days.)

To achieve better light reflection within the shadehouse, use a lighter-coloured shade cloth—e.g., white or beige rather than a dark green or black colour. I’ve used a white-coloured shade cloth for the roof and found it makes a significant difference. However, the shade cloth will discolour if wet leaves are allowed to accumulate on it.

To improve the amount of sunlight reaching the shadehouse during winter, I remove any overhanging tree branches at the start of winter. I also regularly remove any leaves which may accumulate on the shade house’s roof. (My shadehouse has a flat roof to help keep the cost down; however, a “gable”-type roof, such as most houses have, would improve air circulation and help shed leaves.)

For the shadehouse’s benches I followed the following principles:

· If at all possible, keep the plants at least 300 mm above the ground to enable good air circulation;

· The benches should not exceed 900 to 1000 mm in width if they can only be approached from one side—e.g., if they are located adjacent to a wall;

· Heavy “gauge” galvanized mesh is better than most other products for a bench top as it doesn’t rot or rust. (Fortunately, I was able to obtain some second-hand from a shadehouse which was being demolished, otherwise it can be rather expensive.) Further, because the mesh doesn’t rust, bromeliads grown underneath the benches aren’t “burnt” by contact with water containing iron or other contaminants—as can happen if rusty reinforcing mesh used for concreting is utilized.

Most of the Tillandsias are hung on sheets of galvanised mesh suspended from the wall formed by the paling fence. This is similar to the method used by Barry Genn and Nev Ryan, two of Queensland’s most experienced Tillandsia growers, for growing many of their plants. They also suggest having the bottom of the galvanised mesh sheet further away from the wall than the sheet’s top--in other words, the sheet is tilted away from the wall. This reduces the amount of water which drips from one plant onto another when they are watered, which in turn gives you better control over the amount of water each plant receives.

I also have some sheets of galvanised mesh suspended horizontally about 600mm below the shadehouse’s roof. Many of the Tillandsias I have growing in pots and tree fern “logs” like this environment. Also, I have some Tillandsias hooked onto the shade cloth-covered southern wall. They seem quite happy in this environment.

On the floor of the shadehouse I have more light-reflecting material in the form of pine bark chips. These came from Slash Pine and Caribbean Pine trees, and are light brown or orange in colour when new, rather than much darker-coloured bark obtained from Hoop Pine. As it retains moisture when watered, the pine bark also improves the humidity in the shade house. Other light-reflecting material can also be used to good effect. For example light-coloured pebbles can achieve a similar outcome.

I hope these ideas are of some use if you decide to build a shadehouse. I wish to thank Gerry Stansfield, Doug Upton, Barry Genn and Nev Ryan for sharing their experiences with me.

"BUILDING A NEW SHADEHOUSE" Postscript

By Ray (Nicko) Nicholson

(From Bromeliad Society of Queensland Inc.’s May/June 2002 issue of Bromeliaceae, Vol. XXXVI No. 1.)

Because of my ongoing battle with my computer (which usually wins), I sent an incomplete article to Editor Peter—I left out some important paragraphs in my article "Building a New Shadehouse" which appeared in the January-February 2002 edition of Bromeliaceae.

The sandstone-coloured shade cloth I used was 75%, the same percentage most growers use, but in the green colour. As I said in my previous article, the sandstone colour allows much more light through because it “generates” considerable reflected light which green does not. This is fine in winter months, but as last summer approached, I found there was too much light in the shade house as many of my bromeliads were turning a khaki colour instead of green.

To overcome this, I added four-foot wide strips of 75% sandstone at four—foot intervals over the entire roof. These additional strips run north-south because of the angle of the sun’s passage during the course of the day. This helped a lot until those real hot mid-summer days with more intense light when my plants again turned into the khaki colour. The remaining single 75% will now have to be covered with another layer to further reduce the light.

No one could tell me, with any degree of certainty, what two layers of 75% equates to, but if I were to build another shade house using the sandstone colour cloth, I am convinced 90% will be ideal. Even though two layers of 75%, or one layer of 90%, may seem to be too much, the quality of light, according to the growth of my bromeliads, is still a lot brighter and better than the 75% green cloth with its dullish light. I base this on looking at the shade cast by the varying thicknesses and combinations of shade cloth.

I previously said I covered the ground with six sheets of newspaper and then a sheet of weed-control cloth. Because Brisbane is a notorious termite area, the whole area is also covered with one-inch cypress pine wood chips. I stress the use of cypress pine and not pine bark because cypress is a well-known deterrent to white ants while pine bark attracts them. The extra benefit of this allows the soaking-up of more surplus water (rather than letting it go to waste in the ground) and therefore increasing much-desired humidity.

While I have erected some shelves in my bromhouse, I favour cementing into the ground 7-foot lengths of water pipe on which I attach brackets into which fit the pots. There are several advantages in this over shelves: firstly, up to 25 plants can fit on one post which occupies the same areas as one plant on a shelf, thereby dramatically increasing the number of plants in any given area; and secondly, several microclimates are created which means there are many areas available to plants which require different conditions—more than can be achieved on shelves.

LIGHT QUALITY, SHADE CLOTHS …and making your Neos look good.

(Article taken from Bromeliad, The Bromeliad Society of New Zealand journal which was adapted from an article by ‘Brom Spider’ in the Gold Coast Succulent and Bromeliad Society ‘Bromlink’.)

Light quality!! Let’s say you’ve grown some very nice neoregelias and you’re feeling pretty proud of your babies. You take them along to a display and they look flat and lack the sparkle they had at home.

No one will realize your plants are not looking their best except you, their proud owner, and when you get them home again they will look their usual colourful selves. The problem revolves around the quality of light available and this quality affects how our eyes register the colour of the plants. Sunlight in the early morning is bluish/cold, in the middle of the day it is normal and late afternoon reddish/warm. Our eyes will register all this but our brain will adjust all this to a constant normal. Get up early in the morning and if you have a big interest in neoregelias, you will perceive that they glow in the morning light, look normal during the day and in the late afternoon they look good again. This colour change is caused by the quality of the light.

Green Fibreglass: If you know anyone that has green fiberglass, have a look at your neoregelias under these conditions and you will find that it kills the colour stone dead and this colour change is caused by the quality of the light transmitted through the green fiberglass.

Yellow Fibreglass: I doubt if this is still being manufactured, but you never know. If you can find any, have a look at your neoregelias under it. They are magnificent. The transmitted light enhances the colour.

Now go for broke! Take your neoregelias down to the local butcher shop and have a look at them under the pink meat light. They will look absolutely fabulous.

Polarized light is the reflected light of the leaves of the neoregelias from late morning to early afternoon (the middle of the day); for me, very irritating and it spoils my enjoyment when viewing the plants. I prefer the early mornings and my second choice is later afternoon when the polarized light factor is at its minimum. Cloud cover or smog also reduce polarized light.

Black Shade Cloth: I do not like and is no doubt a carryover from my experiences with green fiberglass. This colour variation caused by green shade cloth must be so slight I should place it in the category of prejudice, not fact.

White Shade Cloth: For me this cloth seems to enhance the polarized light problem and that is my only criticism. If this cloth is being used in conjunction with shade from buildings or trees, etc. I consider it the perfect choice.

Sandstone Shade Cloth: Where you have no supplementary shade, this is my cloth of choice. The polarized light problem is still there but although it is less than white, and more than black, there is a plus from the quality of the transmitted light as it enhances the red colour of the neoregelias more than the white and has considerable advantages over the black.

Polarized light is reflected light at a 90 degree angle to sunlight and is very glary. If you are going to have a display bed, it will be best viewed with the sun at your back.

Knitted Shade Cloth: Because of the profile of this cloth, the shade factor (percentage of shade) in the morning and afternoon is greater than midday and in winter in southeast Queensland (more as you move south) the shade factor is greater than summer.

Woven Shade Cloth: Provides a more even percentage of shade (because it has a flat profile) than knitted cloth with the sun’s movement. This type of cloth is provided with a percentage of shade indicated. However, the various colours of cloth are not available.

HELPFUL HINT!

(Extracted from the November 2004 issue of The Hunter District Bromeliad Society Newsletter. Original article appeared in the Florida Council of Bromeliad Societies Inc. ‘Newsletter’, May 1992, author Carol Johnson.)

Most vrieseas prefer to have dry feet. One exception is Vriesea ospinae which needs to be fed regularly and the soil must be kept moist at all times. I over pot and grow with the pot standing in a tray of water. To further demonstrate its individuality, Vriesea ospinae will not bloom naturally unless it is allowed to clump. Most growers forget it. Do not take pups until blooming is past. The plant responds well to Florel and even the smallest offset will bloom, but the natural bloom is superior to the forced one.

Phillip has recently come across a delightful little book which was published nearly 60 years ago. Its title is “PLANT LIFE” and was the second periodical to be published by The American Plant Life Society (VOLUME 1, Nos. 2 & 3, JULY & OCTOBER, 1945 (Published March, 1947). A notation in the front reads: FIRST BROMELIACEAE EDITION, Dedicated to MULFORD B. and RACINE FOSTER in recognition of their outstanding work in collecting and popularizing bromels.

I have found it fascinating and thank Phillip very much for loaning this precious book to me. Below is an article I have extracted from it.

WHERE BROMELIADS ARE FOUND

By Mulford B. Foster

Without a doubt the Andean area of South America mothered the family into existence. While the puyas, the earliest members of this interest group, have devoted their efforts toward survival in their original home area, regardless as to how high they have been pushed up into the clouds, their great line of descendants have migrated all over South America and the southern area of North America.

Whenever we study the migration of birds, men or animals we see a similar pattern, we find men following the plants in low swampy land, in the high mountains, in low rolling hills or on the desert.

Brazil, it seems, has been the favorite place of residence for the bromeliads, as the greatest number of different genera and species are to be found there. And yet, one could travel for days within certain areas without seeing hardly one bromeliad.

The puyas have traveled from Chile to Costa Rica, yet they have not set root in Brazil.

Tillandsia usneoides and T. recurvata, called Spanish Moss and Ball Moss, have been the greatest migrators of all; they now live in every country and state where there are any bromeliads to be found (with the exception of Africa).

In marked contrast to these Tillandsia species that use the most modern way of travel, via air, their relative Vriesea itatiaiae has been so self-satisfied that it lives on Mt. Itatiaya, one of Brazil’s highest mountains and nowhere else on the earth. There are other endemics in the family but few with a range so limited.

The genera Navia, Brocchinia and Bakerantha [now Hechtia] are found north of the Amazon in the Guianas, Venezuela, Brazil and Colombia. They are rare and isolated in habitat.

Cryptanthopsis [now Orthophytum], Cottendorfia and Sincoria [now Orthophytum] are limited to a small area of southwestern Bahia in Brazil.

Encholirium is coastal from below the mouth of the Amazon to Espirito Santo and inland as far as Minas Gerais and Bahia.

Ochagavias are isolated on Juan Fernandez Island off the coast of Chile.

Abromeitiellia and Fascicularia choose high Andean ranges of Chile to be near their ancestors.

Greigia has not left the home ground of the puyas and are to be found from Costa Rica to Chile.

Lindmania, a very early relative of the puyas, has kept close to them but has also gone farther north and on into Mexico as well as around the northern rim of the Amazon basin, but it has not gone down into Chile.

Ronnbergia and Mezobromelia, rare genera, seem to prefer the western part of Colombia.

Deuterocohnia with its few known species is found in the central and southern area of the puyas but has gone over into the Matto Grosso of Brazil. They have shared some of the territory with Dyckia but the dyckias have taken in parts of Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Uruguay and a great area of Brazil as far north as the Bahia area.

Hechtia, though closely related to the puyas, has apparently never trespassed into the Puya domain. They have chosen their territory to be in Central America from north of Costa Rica, with a northern boundary line in lower Texas, Arizona and Baja California.

Pitcairnia, on the other hand, has spread from the central part of Mexico, including the West Indies and a greater part of South America, with its southern limits in the Argentine, Bolivia, and a portion of Chile. Strange as it may seem just one species has been reported in Africa.

In very nearly the same areas as the Pitcairnias dwell you will find the genus Catopsis, excepting that it avoids Chile and some parts of the lower Argentine. Vriesea, too, which has the southern part of Mexico as its northern limit, takes in all of the Catopsis area and a bit more of Bolivia and Peru. However, most of the species are native to Brazil.

The circle shrinks for Guzmania. The northern limit is southern Mexico and the tip end of Florida. The southern limit swings around the northern part of Brazil from Bahia across to the Pacific Coast. It is interesting to note that the Florida species of Guzmania monostachia has taken up residence in much of that area even to Bolivia.

A much smaller inner circle, taking in Costa Rica, a part of the West Indies and the northeastern section of South America, would circumvent the area occupied by Thecophyllum (now Vriesea).

The few species of Glomeropitcairnia are found in a very limited island area of the Lesser Antilles with Trinidad as its southern limit.

Tillandsia, greatest of all migrants in the family, has made a territorial line swinging around all of the species so far named and those yet to be zoned in this treatment. Its very northern limit is the south-eastern tip of Virginia at the 35th parallel; its southern limit in the Argentine to the 45th parallel would be comparable to being in the neighborhood of Maine and Nova Scotia in the North.

One of Brazil’s finest fibre plants, Neoglaziovia, a monotypic genus, is found only in a limited area of Bahia and states bordering its northern boundary. Acanthostachys, another genus with but a single member, is also Brazilian but has a greater range throughout the central section of Brazil.

Disteganthus from French Guiana, Wittrockia from coastal mountains in Brazil, Araeococcus from Costa Rica and northern South America, Pseudananas, the false pineapple found on the high plains of Brazil, all six of these genera have but from one to three species to their credit.

Cryptanthus species are all central Brazilian and the four or five Orthophytum species are to be found in a somewhat similar area. Andrea species too are limited in their central Brazilian home.

With the exception of one Neoregelia (which is in Peru) all of the Neoregelia, Nidularium, and Canistrum are confined to Brazil.

Hohenbergia species are native to Cuba and the West Indies with ten of the species from Jamaica; they range on down through Trinidad and into Brazil. A typical species of this genus, Hohenbergia caatingae, is a stiff-leaved bromel that grows in great masses on the caatinga which is similar to mesquite. It will stand very severe drought.

Wittmackia and Gravisia seem to keep to the Atlantic Coast of South America from northern Brazil up to Costa Rica and into Puerto Rico and the Lesser Antilles.

Androlepis has a Central American residence for its few species, while Streptocalyx seems to be just as satisfied in Peru as in Brazil for its species may be found in the western and northern end of South America right on down to Rio and surrounding country.

Ananas, the pineapple, may be found wild in many parts of Brazil but in just how many of the other countries of South America it was originally native is open to much discussion. At any rate some of the species grow wild over quite an area.

The genus Bromelia covers a great area. Some of its species may be found in Mexico, the West Indies or right on through Central America, over a great part of South America on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. I have found it growing wild in many American tropical countries where almost universally it has been used by the natives as a property line marker where conditions are primitive.

The beautiful Portea species are few in number with a range along the Atlantic coastal region in Brazil from Rio north to Bahia.

The range of the delightful Quesnelia species is from the Guianas to southern Brazil and they do not go inland for any great distance.

The Chevaliera species keep to the Brazilian coastline also.

Most of the Billbergia species find their home in Brazil but they are lightly sprinkled from Mexico south and well down the Atlantic coast to Argentina with a few on the Pacific to Peru.

The Aechmea species are greater in numbers and greater in range than almost any of the other berry-fruit bearing bromeliads; they are native from Mexico south, including the West Indies and throughout South America. Brazil, of course, has by far the greatest number of species.

They are an intriguing family, the bromeliads. They may be found perfectly at home on the side of a house or a perpendicular rock, attached to a giant cactus or a telephone wire, overhanging a waterfall or on a rainless desert.

With or without roots the species will be found, each one finding much of their food in the air carried to them by favorable air currents or rainfall dropped into their water-filled cups far up in the trees and under the trees.

The bromeliads have explored the American Tropics for centuries and have settled down in so many out-of-the-way places that inquisitive plantsmen are still seeking their whereabouts in order to know more about them.

Notes included with article:

Neoglaziovia - Now with three known species, Neoglaziovia burle-marxii, N. concolor and N. variegata.

Acanthostachys - Now with two known species, Acanthostachys pitcairnioides and A. strobilacea.

Currently, Disteganthus has 2 species; Wittrockia 6; Araeococcus 6; and Pseudananas has just 1.

Wittmackia - Now included in Aechmea

Gravisia - Now included in Aechmea

GROWING SMALL, GREY-LEAFED TILLANDSIAS By Bob Reilly.

(From Bromeliad Society of Australia’s BROME LETTER, November/December 2003 issue, Vol. 41 No. 6.)

Tillandsia is the largest genus in the bromeliad family, with over 400 species. Tillandsias have a wide diversity in size and shape. This article discusses a group of plants which I have chosen to describe as the small, grey-leafed tillandsias. They all have silver-grey, silver-green, or grey-green leaves, and do not exceed 30cm in diameter. Nor does the term cover those really small tillandsias normally having a height of less than 5cm or so.

All of the tillandsias discussed in this article have similar growing requirements.

Typically, they all grow best on “mounts” of some type. Pieces of cork slabs have been used extensively by some growers. Other materials I have used include:

· Pieces of hardwood fence palings and flooring (but not material which has been painted or treated with timber preservative). Well-weathered wood is best, as it provides plenty of crevices and cracks for the plant’s roots.

· 2 to 3cm wide callistemon and melaleuca branches which have been dried in a shady place for about a year. The drying process can be accelerated by leaving the leaves attached to the branch.

It is important plants are firmly secured to their mounts. If they are not, the plant is very unlikely to thrive. Methods for securing tillandsias to mounts include:

· Tying them on with strips of light-coloured hosiery (avoid bright colours as they will not “blend” into the plant and mount).

· Gluing them on using a product such as Liquid Nails. However, use solvent-based rather than water-based glues, as the latter product can disintegrate before the plant sends roots onto the mount.

Mounts can be held in position by securing a thin wire “hook” to their tops, and then attaching them to a variety of fixtures. Examples include: sheets of galvanized weld-mesh suspended vertically, shadecloth walls of bush houses, trees, and fences.

The plants described in this article can be grown in full sun for most of the day in southern Queensland during winter and under 50% shadecloth for the balance of the year. (However, they will also grow quite well under 75% shadecloth for the entire year, which is how I grow them.) Positions in the garden which have similar amounts of shade will also produce good results. However, it is important that good air circulation exists in whatever location is chosen for these plants.

Watering once a week in winter, between 7am and 10am, and twice a week in summer between 7am and 10am or 4pm and 6pm, will usually produce good results. Watering at these times enables the plant to dry out before mid to late evening, and thus reduce the chance of rot developing. Where plants are grown in clumps, it is important the entire surface of the clump (including its top and bottom) are watered.

This approach ensures all plants receive water, as they do not share a common root system (which would enable water to be transported from one plant to another).

While tillandsias are often described as “air plants”, they need nutrients to grow and flower. In nature, these are obtained from particles of animal and vegetable matter which are either carried by the wind onto a plant, or which fall onto it. However, the amount of food available from such sources is greatly reduced if a plant is grown in a shade house or on a house veranda.

Nutrients can be supplied through the weekly or fortnightly application of liquid fertilizers. I use, on a weekly basis, a fertilizer which has a Nitrogen (N):Phosphorous(P):Potassium(K) ratio of 14:4.4:2.5. I wet the plant’s leaves before applying liquid fertilizers, as this assists in nutrient absorption.

These plants have few pests and diseases. Mealy bugs and “soft” scale can gather at the base of leaves and old flower scapes. They can be treated by dipping the plant in a commercial insecticide at the concentration recommended by the manufacturer. However, do not use white oil or other oil-based products, as these can kill tillandsias. Grasshoppers will sometimes attack the foliage of these plants. They can be easily killed by the direct application of physical force in the early morning when they are relatively inactive. The periodic removal of dead leaves helps to minimize the chances of rot developing.

These tillandsias produce offsets (pups) in various ways:

· Some tillandsias, for example certain varieties of intermedia, produce pups along, or at the end of, flower spikes (as well as other locations on the plant). Such pups can be detached from the flower spike by using secateurs.

· Other tillandsias, for example geminiflora and gardneri, usually only produce one pup. As this is located near the plant’s base, and very near to its “growing point”, the best approach is to leave the pup on the mother plant. Over time the mother plant will “shrink” in size, and eventually “disappear” into the growing pup.

· Many tillandsias, for example bulbosa, butzii and caput-medusae, readily form clumps. While these can be separated by “teasing” the plants apart, such species often look their best when grown as clumps.

· Some tillandsias produce pups near the plant’s base. Unlike the first category of tillandsias described above, these pups can be removed by gently easing them away from the plant when they are about half the parent’s size. Examples are ionantha, albertiana, crocata and streptocarpa.

· A number of tillandsias grow on long stems (this is known as a “caulescent” growth habit). Pups occur along these stems and can be removed with secateurs. Examples are bergeri, aeranthos, and tenuifolia.

· Some tillandsias, for example disticha, produce pups at the end of stolons. They can be removed by cutting the stolon, with secateurs, about 2cm from the pup’s base.

In preparing the plants’ descriptions, I have drawn heavily on the following books: Isley (1978), Oliva-Esteve (2000), Rauh (1979), Shimizu & Takizawa (1998). The titles of these books are given at the end of this article.

T. aeranthos. While this is a variable species in terms of its size and inflorescence, a typical plant averages 12cm in diameter and height. Over time it grows outwards along a stem. The leaves are silver-grey, and spread in all directions from the stem. It is easy to confuse this plant with T. bergeri when they are not flowering. The small inflorescence sits on top of a stalk (floral scape) which raises it just above the plant’s leaves. Red floral bracts surround each of the 10 or so flowers which are deep blue in colour. This plant is easy to grow and readily forms a clump.

T. albertiana. Each plant resembles a small tuft of grey-green leaves on a stem. Plants are usually 5 to 10cm tall and wide. Each plant has one cherry-red bloom which is about 1 cm wide. Unlike many tillandsias, the bloom lasts for over a week. The plant rapidly forms a clump.

T. bergeri. This species eventually produces stems, over 30cm long, with the current “plant” being at the stem’s end. Each plant is about 12cm wide and high. Leaves are silvery-grey in colour. The inflorescence emerges about he leaves and consists of a small cluster of about 10 flowers with white and violet petals. The floral bracts are often a pale pink. This plant appears to need good light to flower well. I have a clump grown under 75% shadecloth which produces few flowers compared with one which receives the full morning sun throughout the year, and filtered light in the afternoon. The plant rapidly forms a clump over 60 cm in diameter. Ultimately, the weight of the plants causes the clump to fall apart.

T. brachycaulos. About 30 grey-green leaves form a 15cm wide and 10cm high rosette. At flowering, the entire plant turns a bright red. The flowers, which have violet-coloured petals, form a cluster in the plant’s centre.

T. bulbosa. The plant is very variable in size, but typically reaches 15cm in height and 12cm in diameter at maturity. (However, there is a miniature form which only reaches 7cm in height.) About 6 leaves form a “bulb” at their base and then arch outwards. The leaves’ colour is quite variable, with some plants (clones) having grey-green leaves while others are a silvery-grey. When the plant flowers, the upper leaves and inflorescence are cherry-red in colour. The inflorescence consists of a multi-branched spike, with each “branch” being about 5cm long. The flowers have blue petals. This plant readily forms a clump.

T. butzii. The few leaves are typically up to 30cm long and form a “bulb” about 5cm long at their base. The inflorescence consists of a single pink spike about 15cm long and 1cm wide, while the flowers have violet petals. This species readily forms a clump. It is very variable in size. Some clones have multi-branched spikes.

T. caput-medusae. At maturity this plant is 15 to 40cm high and 15 to 30cm wide. Most forms have up to 10 light green leaves, typically rising from a bulbous base about 5cm wide and high, although some are much larger. At flowering, a cluster of 6 to 8 small pink to red spikes up to 15cm long and 2cm wide emerge from the plant’s top. The flowers have blue petals. This is a very variable species. However, the smaller forms, in particular, readily form clumps which are quite decorative even when they are not in flower.

T. cacticola. A mature plant is often about 10cm high and 20cm wide. About 15 silver-grey leaves form a “flattened” rosette. The inflorescence rises from a 25cm long “stalk” and consists of 5 to 8 lavender-pink spikes, each of which is about 10cm long and 3cm wide. The flower petals are white, with violet tips. The long-lasting colouration of the spikes make the plant well worth growing.

T. crocata. This species rapidly forms small clumps. Mature plants are 7 to 15cm in height and width and appear like small tufts of silvery-grey leaves. A few aromatic flowers appear at the end of a 10cm long stalk. The flower’s colour is typically a pale to deep yellow.

T. gardneri. Around 20 silvery-grey leaves form a rosette about 20cm high and 15cm wide. The multi-branched spike is located at the end of a 15 cm long stalk. Each of the pink, elliptically-shaped “branches” is about 6cm long and 3cm wide. The flowers have pink-red petals. This species, while attractive at all times, is quite spectacular when it flowers.

T. intermedia. This few-leaved plant has an elongated, bulbous base about 20cm long and 3cm wide. The overall height is about 30cm, while the leaves are grey-green in colour. A multi-branched spike rises just above the leaves. Each branch is pale pink and is around 10cm long and 4cm wide. The flowers have violet-purple petals. Several generations of plants may be alive at any time. In some clones, these may form a “chain” of plants several metres long. This plant may be in some collections under its old name: T. circinnata.

T. ionantha. Up to 40 leaves typically form a dense rosette from 4 to 10cm high and 2 to 5cm wide. The leaves are normally silvery-green in colour (although the variety stricta has reddish leaves) until it flowers. At that point, the top half of he plant usually flushes red, although many clones turn red all over. Two to four flowers with violet petals emerge from the top of each rosette. However, there is a form (called ‘Druid’) with white petals, with leaves which turn yellow, rather than red, at flowering. This species is quite variable in size and growth habit. However, its long-lasting red colouration in the middle of winter (which is when many clones flower, although some flower in spring and early summer), and “no fuss” growing requirements, make it a very popular plant.

T. ixioides. About 10 silvery-grey leaves form a semi-erect rosette around 15cm wide and 10cm high. Four to 10 yellow-petalled flowers are clustered at the end of a 7cm long stalk (floral scape).

T. streptocarpa. The 10 or so silver-grey leaves form a plant about 25cm in height and width. Mature leaves have curled tips. The inflorescence forms at the end of a 20cm plus stalk and consists of 5 to 8 linear clusters of around 6 flowers each. The fragrant flowers normally have blue petals, although there is a form with white ones. This species is quite variable in size and appearance, but is well worth growing for its foliage and fragrance at flowering time.

T. stricta. Numerous, typically grey-green (but often silver-grey) leaves form a rosette 10 to 20cm wide and 8 to 12cm high. The arching inflorescence forms at the end of a 5-10cm long stalk and consists of up to 10 flowers surrounded by pink to red bracts. The flowers typically have blue or purple coloured petals. This is a very variable species with respect to size, leaf colour and bract/petal colour. Some clones will readily form large lumps of 50 or more plants. When they are all in bloom, the clump makes a spectacular sight. There are summer and winter-flowering forms of this species.

T. tenuifolia. This species typically has a stem about 20cm long, while its width is 3 to 5cm. The leaves are like short pine needles and are usually green, although a dark red to black form is also available. A small cluster of up to 10 white-petalled flowers, surrounded by pink to red bracts, forms the plant’s inflorescence. It sits at the top of an erect floral scape which rises above the plant’s leaves. (There is also a form which has flowers with blue petals.) This variable species is easy to grow. It is quite interesting because of its long stem relative to its width.

All of the plants described above are easy to grow and can be obtained easily from a number of sources. They could easily form the basis of a small tillandsia collection.

Acknowledgements :

I thank Nev Ryan for his help in preparing this article.

Bob Reilly

REFERENCES :

Isley, P.T. (1987) Tillandsia: The World’s Most Unusual Air Plants. Botanical Press, Gardena, California.

Oliva-Esteve, F. (2000) Bromeliads. Armitana Editores, C.A. Caracas, Venezuela.

Rauh, W. (1979) Bromeliads for Home, Garden and Greenhouse. (English Ediotion edited by Temple, P.) Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset, England.

Shimizu, H. & Takizawa, H. (1998) New Tillandsia Handbook. Japan Cactus Planning Co. Press.

Elizabeth’s Spinach Damper Snack

1 round cottage-type loaf of bread

1 small white onion, finely chopped

1 carton sour cream

1 packet frozen spinach, thawed and well drained OR 1 bunch fresh spinach leaves, cooked, well drained, and finely chopped

1 packet Continental Brand Spring Vegetable Soup

Pepper

1 cup mayonnaise

1 cup grated cheese

Dash of lemon juice

Combine all of the ingredients, except the bread, together.

Just before serving fill into the crusty bread round, which has had the top cut off and some of the middle taken out.

Cut these up and serve around edge of plate for dipping.

Anyone who’s been a member of BSSF for any length of time will know the name Wally Berg.

Wally was a resident of Sarasota, a serious and self-taught bromeliad enthusiast who explored Latin America and maintained one of the best bromeliad collections in the world. He grew bromeliads throughout his yard and in a screened area behind the house. A magnificent old oak tree shaded the front yard, and high in the branches Wally had mounted all kinds of bromeliads, large and small, creating a colorful jungle in the sky. His place was a Mecca for scientists, collectors and just plain folk who loved bromeliads.

After he died five years ago, his widow Dorothy sold their home and moved to an apartment. The collection was dispersed to other growers around the country.

In August, the house was sold again and the buyer bulldozed it.

The next day the old oak tree was cut down. … …

Wally’s yard was an inspiration to all who visited. Many people who created their own bromeliad beds tried to emulate his sense of color and harmony. He was such an accomplished grower, it was no surprise that he routinely walked away with all the top prizes in shows and World Conferences.

Wally and Dorothy kept a photographic record of their place and you can see the way it was on the FCBS web site at fcbs.org On the menu on the left, click on Photo Index, then scroll down to the bottom (under Programs) to the Berg Cage.

Furthermore, they do it in the opposite way from conventional plants. Their greatest cleansing activity is at night, during darkness or low light levels.

The results of research on the topic by scientists at the Wolverhampton Environmental Services, Mississippi, were reported recently.

Orchids and bromeliads, commonly called Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM) pathway plants, use carbon dioxide in the directly opposite way from ordinary plants.

During photosynthesis, most plants open the respiratory stomata on the undersides of the leaves, extracting carbon dioxide for use and exuding oxygen and water vapour. Many hot, dry desert plants close the stomata during the day when they would be likely to lose too much moisture, and open for business, so to speak, at night.

Hence CAM pathway plants exude oxygen and take in carbon dioxide at night, reversing the process during the day. The value of this process in cleansing polluted air was demonstrated by putting a range of plants in sealed plastic chambers and introducing acetone, ammonia, chloroform, formaldehyde, methyl alcohol, ethyl acetate and xylene. Acetone, ethyl acetate and methyl alcohol are bioeffluents emitted by humans. Formaldehyde and xylene are emitted by some modern building materials. Sampling was undertaken every hour at noted temperatures.

Orchids were efficient at removing formaldehyde and xylene from the chambers, only being beaten on formaldehyde by a bromeliad. Both the orchids and the bromeliads removed larger quantities of xylene during the dark phase, showing that open stomata increased their ability to remove pollutants.

The scientists recommended mixing CAM and non-CAM plants to stabilize day and night carbon dioxide and oxygen levels in tightly sealed buildings 24 hours a day.

DON’T THROW THEM AWAY

By Bea Hanson, Auckland

(From Bromeliad Society of New Zealand Inc.’s Journal, March 1997 Vol.37 No.2)

Before the Bromeliad Society was formed, a few of us, all member of the Cactus & Succulent Society, became very interested in bromeliads. None of us knew much about them, books were scare and so we more or less lumped the broms with the cacti and watered the lot together. Looking back, it says something for broms and how they can stand tough conditions!