1992 - 2012

NEWSLINK - JANUARY 2012

1992 - 2012

NEWSLINK - JANUARY 2012

At our March meeting we will celebrate the 20th Anniversary of the formation of our Society. It all began after an article appeared in the Advertiser newspaper to let Illawarra residents know of the possibility of starting up a local bromeliad society in the area. This article had been at the instigation of Merv Henderson, a member of the Bromeliad Society of New South Wales, whose dream it was to introduce more people along coastal New South Wales to the beauty of bromeliads. And so it was that on February 1, 1992 about 20 people met at the Education Centre of the Wollongong Botanic Garden to discuss this proposition. Tremendous support was also given by other members of the Society, many of whom travelled down to stage a very beautiful exhibition of bromeliads in readiness for the visitors who would attend the meeting. It was apparently a most inspiring, friendly and successful occasion and Merv’s aspirations were fulfilled as the Illawarra Bromeliad Society was formed, the inaugural meeting being held on March 7, 1992.

At this March meeting Jeff Bartley was elected President, Rob Stone, Vice President, Peter Rieck, Secretary, and Bob Gray, Treasurer. Later, Steve Popple, then Curator of the Wollongong Botanic Garden, was approached regarding becoming our Patron, a position which he accepted. Unfortunately, due to health problems, Peter Rieck was unable to continue as Secretary beyond February 1993 and Margaret (Bartley) was elected Secretary at that time. During the first year all kinds of details needed to be attended to and I can only imagine the amount of work which would have gone on behind the scenes to make all of these things happen; however, Margaret remembers it as being fun! There was a lot of excitement and things got off to a flying start, with people like Margaret and Jeff, Dulcie Doonan, Enid Whalley, Nina and Jarka Rehak, Phillip Robinson and Robin (Bob) Gray organising in many different areas. This fledgling Society, in its first year, participated in the Florawarra festival (an event which was held each October at the Wollongong Botanic Garden) as well as putting on displays at the Corrimal Shopping Centre and Shellharbour Square. Margaret described Dulcie and Enid as stalwarts (I remember Enid as our dedicated Librarian and Dulcie ‘wore many hats’, including Publicity Officer, Committee member, bus trip organiser, refreshment supply officer, show steward, and recorder of monthly plant competition details. Nina and Jarka and Bob and Bridgit Christoffel were members of the New South Wales Society who came with plants and knowledge to share with this new Society, Bob and Bridgit regularly travelling from Hornsby Heights. Beth Churton and Glad Colquhoun also drove long distances, coming all the way from Culburra Beach, and were another two of our founding members, along with Hans Kutzner, whose daughter, Susan, designed our logo and Marj Rickard, who organised our bus trips for some years.

During the second year the competition table with a trophy being presented for most points was introduced (Dulcie was the first winner), and our Society was invited to participate both in the Wollongong Horticultural Society’s Autumn Show as well as ‘Florawarra’. Also going on was liaison with Steve Popple and the Wollongong Botanic Garden to have the roof of the glasshouse replaced and donation of bromeliads by our Society for display in this structure, as well as to start a bromeliad section in the garden outside. And so it went - designing our logo, arranging displays at Corrimal Court, Bulli’s Heritage Week celebrations and the Performing Arts Centre, etc. and Bob working on the process of Incorporation.

Recently, while going through some old paperwork I came across the original die, designed by Susan Kutzner, which was used to have our Society badges made up. The design features a drawing of Vriesea pulmonata (but now thought to be Vr. ‘Poelmanii’) and I have used this as our cover for this issue of Newslink.

In 1998, when Florawarra became no longer viable and had to be cancelled, an invitation came from the Corrimal Chamber of Commerce to take part in the “Spring into Corrimal” festival, and with their help we found our new location, which we have been using since - the Uniting Church Hall in Russell Street, Corrimal.

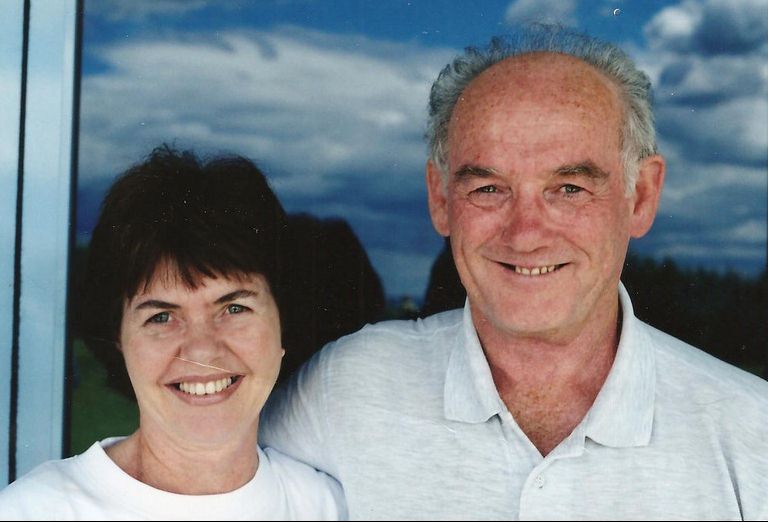

Margaret and Jeff continued as President and Secretary until our July 1999 Annual General Meeting when they resigned to make the move to Mackay. Eric Jordan was elected our new President; Graham Vice-President; Valery Jukes Secretary and Val Dixon Minutes Secretary. I stepped in as Secretary in February 2001 and Graham and Elizabeth were elected President and Treasurer at the July 2001 AGM, Elizabeth taking over from Bob Gray, who, tragically, lost his house and fantastic bromeliad collection in a disastrous bushfire on Christmas day of that year.

The year 2001, however, was a milestone year for our Society for in October we hosted Brom-A-Warra, the 11th Conference of Australian Bromeliad Societies, at the Sea Spray Function Centre in Shellharbour. Dr. Eric Gouda, Curator of The University of Utrecht Botanic Gardens in The Netherlands was our international guest speaker and other speakers came from Cairns, Townsville, Brisbane, South Australia, New Zealand, and our own John Fleming whose talk on growing tillandsias in the Illawarra was particularly well received.

When membership increased to the point where we needed a larger venue for our meetings we moved, in February 2007, to the Dapto Ribbonwood Centre where we seem to have gone from strength to strength. And now we celebrate our 20th year and none of it would have been possible without the commitment of our members to step up to take care of whatever has been needed to be done. Ours is a fortunate Society, I believe, as we have always had that willingness and commitment from our members to make it the friendly, interesting forum that we have today and I am confident that we can look forward to the next 20 years.

NEWS IN BRIEF . . .

It is with a sad heart that I report that Glenise died on Tuesday, January 24 after a twelve-month battle with cancer. Even after she was diagnosed and undergoing chemotherapy, Glenise attended as many meetings as she could and also came to help us with set-up for our Show in September. She had been friends since kindergarten with our member, June Smith, and they had both joined our Society in September 2006 at our Show. Glenise had a real flair for placing plants so that they were shown to wonderful advantage in her garden and she liked to visit gardens and Shows with June. She also loved spending time with her grandchildren. |

| Jørgen Jakobsen, Steven Dolbel, Betty Ellis, Heather Thain | |

| Meri Stefanidakis, Jim Beverstock, Christa Thomas, Peter Netting, Ian Chinnock | |

| Noel Kennon, Gino Di Cesare, Janine Varley, Rhonda Patterson, Colleen Claydon | |

| Judy Schutz, Jim Clague, Sylvia Clare, Joan Banks, Maureen Wheeler | |

| Vicki Joannou, Anna Stewart, Phillip Robinson, Steve Morgan, Hetty Kerstholt | |

| Freda Kennedy, Dot Payne, Elizabeth Bevan, Jarka Rehak, Sandra Southwell | |

| June Smith, Yvonne Perinotti, Christine Okoniowski, John Carthew, Russell Dixon | |

| Fred Burrows, Maadi McKenna, Sharyn Baraldi, Eunice Spark, Loreen Whiddett | |

| Lyndell Gollings, Eileen Killingley, Neville Wood, Glenrae Barker, Alexi Aleuras |

POINTSCORE WINNER:

Our new member, Chris Butler, took home all of the Points Score trophies for 2011 and he must be congratulated for his enthusiastic participation in our monthly competitions. Chris has brought in some extremely interesting plants for us to learn from and enjoy and we thank him and all of our other members who have participated each month.

LIFETIME MEMBERSHIP AWARD:

It was a great honour for me to be awarded Lifetime Membership at our Christmas party in December. I really believed, however, that Graham and Elizabeth should have been standing up there with me, because it has been a team effort over the past ten years or so. I also could not have managed without the wonderful assistance given me by Val as Minutes Secretary for 10 years, and more recently, Ann, and Sylvia has become my stalwart friend over the years as we handle the registration and competition side of our Shows. Sometimes, though, I wonder if the Illawarra Bromeliad Society hasn’t given me more than I have given it - friendships, conferences, and the push to exercise the ‘old grey matter’ to prepare Newslink, talks, etc. My husband, John, has also been of great help and support in all things bromeliad - from troubleshooting problems with the computer, helping me with any pictures which appear in Newslink, including, of course, the cover), readying and packing the car for my monthly trips to the Illawarra and putting in watering systems/electric fences, etc. to help keep my collection of bromeliads safe and growing. While I’m thanking people, I can’t forget our daughter, Lara, who, since the October 2009 issue, has been printing the colour covers of Newslink for us. I thank you all!

LIBRARY:

Along with this issue of Newslink is an updated list of books available for borrowing from our Library. While some books (those which have not been taken out for four years) have been moved to storage - they are still available should a member particularly like to borrow one and they can do this by putting in a request for a particular book or DVD to Graham or Elizabeth. Unfortunately, those items in the list marked with an asterisk (*) are missing and we would like to ask members to check to see if they might still have them at home, and to please return them by the next meeting or as soon as possible.

Of particular concern is that our copy of the New Tillandsia Handbook by Shimizu and Takizawa is missing, a book which is now out of print but remains an important reference for our members.

WORKSHOP/WORKING BEE:

This time we are planning something different as Neville has very kindly arranged a working bee for us at the Illawarra Light Rail Museum and this promises to give us a very hands-on experience of dealing with some landscaping, garden layout, and even plant mounting skills as there are plenty of trees throughout the garden. (If anyone has a plant or plants they want to get rid of Neville was sure they could find somewhere to plant it here - as long as it’s not Aechmea gamosepala, as there are already plenty in the garden!) The working bee is scheduled for Wednesday, February 15, with the usual times of between 10.00 am and 2.00 pm and anyone interested is invited to attend. Bring your lunch - barbecue facilities are available - and something for morning tea would be appreciated. Also, as the Museum is located in a small melaleuca forest, sometimes mosquitoes can be quite bad so insect repellent is advised.

When coming from the north, proceed south down the main highway and continue south over the Macquarie Rivulet and through the shopping area of Albion Park Rail. Continue along until you go over a slight rise and at the bottom there are traffic lights with McDonald’s on the left. Turn right at these traffic lights and into Tongarra Road and proceed along this road for about one kilometre until you come to the entrance of the Illawarra Light Railway Museum on your right. It has a white post and rail fence at the front and an old light blue steam locomotive inside.

From the south, travel north along the main highway until the Oak Flats interchange. Pass beneath the interchange and continue for about two kilometres until you come to a set of traffic lights, with McDonald’s on your right. Turn left here into Tongarra Road and then follow the directions as above.

The area where we will be has landscaping and plantings and is sheltered from the hot sun beneath paper bark trees at the rear of the brick toilet block and cars can be parked within view anywhere in that area. For morning tea and lunch we can go into the main park as Neville has the gate key. There is a large picnic shelter with a tap and a power point if we need to boil water.

COMING EVENTS:

| HILLS DISTRICT ORCHIDS AUTUMN OPEN DAY – 183 Windsor Road, NORTHMEAD (Next to “The Home Team”). Rare and unusual plants and orchid species and supplies. Ph:9674 -4720 or www.hillsdistrictorchids.com. Park in Mary St. or Windermere Ave. Hours: 9 am – 4 pm. (Ed- Introduce yourself to Ian Hook(me) at 6 Mary St. if I'm home.) | |

| SOUTH AMERICAN NATURETOURS- www.southamericanaturetours.com Including Southern/Northern Ecuador; Argentina and Chile; South Africa. | |

| Royal Easter Show, HOMEBUSH – Participation by New South Wales Society | |

| BROMELIAD SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES AUTUMN SHOW. Senior Citizens Centre, 9-11 Wellbank Avenue, CONCORD. | |

| BROMELIAD SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA AUTUMN SHOW - BURWOOD RSL. | |

| ILLAWARRA BROMELIAD SOCIETY – SPRING SHOW – Uniting Church Hall, Russell Street, CORRIMAL. | |

| BROMELIAD SOCIETY OF AUSTRALIA SPRING SHOW – BURWOOD RSL. | |

| BROMELIAD SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES SPRING SHOW - CONCORD |

20TH World Bromeliad Conference - Orlando, Florida - Caribe Royale Hotel September 24 – October 1, 2012 Early Bird Registration Rate (before 28 February 2012) for BSI Member: US$160 For non-member (countries outside US) US$210 (includes BSI membership for 1 year) Registrations March 1-August 24, 2012: Member US$175/Non-member US$225 After 25 August 2012 and at the door: Member US$200/Non-member US$250 |

AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND FRIDAY MARCH 15 - MONDAY MARCH 18, 2013 Register your interest at: coolbroms@bsnz.org for all the latest conference news or Visit website: www.bsnz.org Early Bird Offers: Before March 31, 2012 NZ$260; April 1 to December 31, 2012 $NZ$280 World Class Conference Presenters Already Confirmed: Elton Leme [renowned author and collector of bromeliads], Brazil Michael Kiehl [growing, creating and supplying wonderful broms for over 20 years], USA Jose Manzanares [author of the beautiful books, Jewels of the Jungle], Ecuador Andrew Maloy [New Zealand’s leading hybridizer of exotic patterned leaf vrieseas] Also, Harry Luther, USA, Nigel Thomson, Australia, and Hawi Winter, New Zealand |

MEETINGS:

PLANT RESULTS - October 1, 2011

OPEN

| Graham Bevan | Vriesea Vogue | |

| Noel Kennon | Aechmea recurvata | |

| Chris Butler | Catopsis minimiflora | |

| Chris Butler | Billbergia Dr Oeser |

| Chris Butler | xNeophytum Galactic Warrior | |

| Gary and Colleen Claydon | Guzmania hybrid | |

| Maria Jakobsen | Neoregelia Jewellery Shop |

| Chris Butler | recurvifolia v. subsecundifolia | |

| Suzanne Burrows | recurvifolia | |

| Sandra Southwell | bergeri, White Star & schiedeana on log | |

| Lydia and Ian Chinnock | cyanea |

PLANT RESULTS - Nov. 5, 2011

OPEN

| Chris Butler | xNeophytum Galactic Warrior | |

| John Carthew | Vriesea hybrid | |

| John Carthew | Vriesea Splenriet |

| Laurie Dorfer | Aechmea filicaulis | |

| Gary and Colleen Claydon | Guzmania Sunnytime | |

| Lydia and Ian Chinnock | Aechmea caudata v. eipperi |

| Suzanne Burrows | seleriana | |

| Chris Butler | fasciculata | |

| Sandra Southwell | (Labeled fuchsii v. fuchsii | |

| Chris Butler | calcicola | |

| Chris Butler | linearis (Small form) | |

| Laurie Dorfer | duratii var. saxitilis |

USING ALL AVAILABLE SPACE :

....Neville Wood, Illawarra Bromeliad Society - 2012

Some time ago now when I found I was running out of bench space in my shade house, I was considering different ways to fit more plants in without crowding them too close together and impacting on their health due to poor light and air circulation. Then it finally dawned on me that in the wild, when growing in their natural habitats, they are growing at all different heights and light levels--i.e., on forest floors, cliffs, tree trunks and overhanging tree branches - and this is when I thought, "I can also grow them at different heights and make use of all available vertical space."

When I mentioned my idea to a few other growers I was told it was very risky, mainly because water overflowing from the high plants would fall onto the lower ones, which could also transmit any disease they may have. The lower plants would be getting extra water falling on them from the plants above them as well. My argument was that this type of thing happened in the “wild” and, besides, if they were growing suspended at different heights, they would have better air circulation and the chance of disease would be minimised because the plant’s health would be improved and thus its chances to combat any disease. As for the claim of the lower plants getting too much water I could simply hang the smaller pots at this level as they dry out quicker and can use the extra water anyway. My main reasoning was that a common problem with broms was rot caused mainly by overcrowding on benches and the resulting poor air circulation which caused the plant to stay too wet. With the plants hanging, and air circulating all around, this wouldn’t be a problem and the plants would dry out quicker with this extra air circulation.

It had got to the stage with my plants that I had to do something to prevent overcrowding, so I decided to give it a go anyway. I reasoned that “nothing ventured, nothing gained” and I purchased a couple of bundles of plastic pot hangers and set about providing suspension points along the overhead roof timbers from which I planned to hang the plants. These were simply protruding screws or flat headed nails which were located nine inches apart to comfortably accommodate the 13 cm pots I use. Finally I fitted the hangers and commenced hanging up the excess plants, and it didn’t take too long for all the plants to be in situ, hanging from their respective suspension points on the roof timbers.

The only problem was that I still had more plants than suspension points to hang them from and I soon found myself looking for yet more space. The answer came in the form of extra suspension points equally spaced between the original ones. But to overcome the crowding problem of these extra plants being too close to the ones already in situ I would need to hang them at a different level so that the leaves weren’t touching the plants next to them.

To achieve this I had to extend the distance from the hanger to the suspension point and this was achieved with a simple piece of thin galvanised wire with a small hook on each end. (Never use copper wire or any other copper products near broms as it is toxic to them and contact with it will eventually kill the plants.) The galvanised wire was strong enough to easily support the weight of the pot, was cheap to buy and was easy to work with. I did foresee a problem with the wire, though, as I realised that in windy weather the pots would move and the wire could possibly damage or even cut the leaves of the plant above it. To eliminate this risk the wire was covered with 3.9 mm black plastic tube of the type used in home irrigation systems. (It’s commonly called spaghetti tube and is available at Bunnings and similar type stores and is quite inexpensive.)

There was also the possibility of a second risk because if the leaves were regularly making contact with the galvanised wire, or runoff from it during watering, they could suffer burning from the zinc in the galvanising. So to overcome this, the wire was first soaked in common household vinegar for a couple of hours to neutralise the zinc (the toxic component of the galvanising). Once the wire hangers were finished and in place I found I could now hang plants successfully at a second level, thereby doubling the capacity of my hanging plants. I have found that the plants requiring more light are best hung at the higher level and the ones requiring less light can be grown at the lower level or on the benches and it’s easy to experiment with different light levels and find out each plant’s preferences.

After a plant count I was amazed to find that the number of hanging plants now totals 357 which is slightly more than those on benches, so I now have effectively doubled the available accommodation for my plants. I have been using this method for three years to this date and I haven’t lost any plants from disease as was originally suggested to me by fellow growers.

So, if you’re running out of space, “look outside the square” and consider hanging some of your plants from the overhead timbers.

TILLANDSIA DISTRIBUTION AND HABITATS

By Laurie Dorfer, Illawarra Bromeliad Society - 2012

Distribution: All tillandsias are native to the Americas, which include the United States, Central America and South America. They range from 38° north, from Virginia in the southern United States, to a southern limit of 44° south in Chile and Argentina in South America.

Comparative to Australia, this incorporates our most northern latitude to our most southern latitude – from Cape York to Tasmania.

Of a general genus overview, they are most diverse in tropical America, including Central America and northern parts of South America, including Costa Rica, Columbia, Ecuador, Peru and south-eastern Brazil. This is comparative of Brisbane to Cape York – although the topography provides a much more varied temperature range than we would typically expect within Australia.

The grey-leaved tillandsias, which are generally more commonly known and collected, are said to be more abundant within an arc from southern Argentina, through Brazil to Venezuela and Columbia, as well as into Mexico, central America and southern United States.

General distribution is limited by temperature to the north and south and oceans to the east and west (Pacific and Atlantic Ocean to the left and right respectively). Temperature not only restricts their latitudinal limits, but altitudinal as well.

Local distribution is generally limited by three determining factors, namely temperature, light and moisture. Because of their predominant epiphytic habit, moisture is the most important. As an epiphyte, they cannot survive long dry periods without atmospheric moisture. This moisture–availability is not just restricted by the form of rainfall as, due to their morphological adaptations with the presence of trichomes, they are able to utilise other forms of atmospheric moisture—more commonly includes humidity, fog and/or dew.

The most prevalent and widely distributed tillandsia is T. usneoides, whose distribution reaches both the northern and southern latitudinal limits, from Virginia to northern Chile and central Argentina. It holds the record for the greatest area colonised of any tillandsia species. Tillandsia recurvata likely follows, which ranges from southern USA to Argentina and Chile. The reasons for such wide distribution of these two species are most likely because of the ability to not only propagate via seed but also vegetatively through stem fragments by the former, and an abundant production of self-set seeds, widely dispersed by wind and birds with an ability to grow on an assortment of substrates for the latter. The subgenus Diaphoranthema, to which both T. usneoides and T. recurvata belong, has the greatest distribution range of any subgenus. These have small inconspicuous flowers which consistently self-pollinate, and therefore produce many seeds.

Some species may grow in the millions, over thousands of square kilometres e.g., T. purpurea and T. palacea, while a few are just confined to a single valley or mountain range.

The areas where tillandsias grow support some of the most diverse habitats, which are predominantly due to topography. Mountains are common and form a distinct part of these areas. The hot, moist lowlands may support just one climatic zone, while the mountains and valleys include a whole range of climatic zones with numerous niche habitats resulting in an incredible diversity of flora. This is why tillandsias are most abundant in the mountainous areas. The Amazon Basin with its many thousands of kinds of plants have very few tillandsia species, whereas mountainous areas like Costa Rica and Ecuador support a much greater proportion.

The two main reasons that tillandsias have such a wide geographical distribution are:

1. Adaptability

They are extremely tolerant and adaptable plants. They have been able to adapt and colonise many diverse habitats, due predominately to their morphological adaptations. The presence of trichomes, CAM photosynthesis, water storage ability etc, all allow these plants to colonise areas which would generally not be capable by your typical plant–even cacti don’t survive in some of these habitats. These specialised adaptations allow access to unconventional sources of moisture and nutrients and economise such during periods of shortage, allowing them to survive and grow in a much greater range of habitats.

They can be found growing from rainforest to deserts, from sea level to over 3000 m, as epiphytes to terrestrial, from high light to low light, etc. Due to this adaptability, an assortment of many habitats have been colonised by tillandsia species.

2. Plumose seeds

Tillandsias produce seeds with an appendage called a coma hair. This resembles and acts as a parachute which enables them to be transported by wind for long distances. As many tillandsias grow in areas where winds are frequent and which often provide the atmospheric moisture, the opportunity exists for seeds to be carried long distances, again broadening their distribution.

Because of their wide distribution and varied habitats, they vary greatly in habit, size and leaf/flower structure. This is why the general appearance among the species is so diverse and that they are the largest genus in the family. The smallest can range in size from just a few centimetres (e.g., T. bryoides) with the largest to over 2-3 m (T. grandis) when in flower.

Also, due to this diversity, many different varieties and forms of one species exist e.g., T. capitata, T. brachycaulos, T. fasciculate, T. tenuifolia, etc., which just makes it even more interesting for the collector.

Habitats

Tillandsias colonise an extremely diverse range of habitats, from tropical rainforest to nearly rainless coastal deserts and most in between.

Many live at mid-mountain to highland altitudes with the greatest abundance between 1500 m to 2500 m above sea level. Atmospheric moisture is one of the primary requirements for such diversification at mid-altitude. This is primarily the result of warm air masses moving up the mountains, which cools as they ascend and condense forming rain shadows. This typically occurs locally, generally reaching only a few hundred metres. These conditions can be easily observed by the presence of epiphytic plants which are reliant on this moisture availability.

These diverse areas are generally forests or open woodlands that are seasonally dry (in terms of rainfall). However, regular moisture by humidity/mist, etc. occurs as clouds which regularly enshroud these areas, all but the highest mountains for at least several hours per day over most of the year. Above 3000 m, temperature is generally too low for growth, even survival.

They are far less common in rainforest environments. The primary reasons for this is that regular rainfall may dislodge seedlings, or as seed is dispersed by wind they are often washed to the ground before becoming airborne, and over-leaching as nutrients are limited by the constant removal of accumulates. Another explanation is the absence of cool nights which are supposedly necessary for CAM photosynthesis.

Apparently warm cloud forest of rather modest annual precipitation provides the ideal habitat for the tillandsias. Here, they maintain adequate moisture supplies without being subject to heavy and constant rains.

Some are located close to the oceans which are fully exposed to the most extreme elements, including regular salt spray. None can withstand prolonged sub-freezing, however some are adapted to high tropical mountains and plateaus where alpine nights can be frosty. Also, many desert situations may reach freezing temperatures at night, although they provide the warm sunny days essential for growing in such conditions. Many of these desert situations provide extreme heat and very little rainfall; the plants therefore rely on the dew which forms early morning after such cold nights. This state of moisture availability is most often at times the only moisture available to these plants, being essential to their survival.

Actual habitats can be divided into many categories, however in their broadest sense; they can generally be divided into 5 categories:

• Coastal Plains

• Mangroves and Swamps

• Rainforest

• Montane (the lower vegetation belt on mountains), including Cloud Forest

• Desert (Coastal Desert and Semi-Desert)

These can be further broken down into more specific vegetation types; however for the purpose of this article, these 5 categories fit most.

Coastal Plains

These are situated along coastal strips, often as front line plants which are exposed to onshore breezes and sprayed with salt water. They are typically found only a few metres above sea level and are most commonly observed in Brazil and Chile, growing on rocky cliffs of the shoreline. The most common species are T. neglecta and T. gardneri var. rupicola.

Mangroves and Swamps

These typically occur in salt water tidal areas, river outlets and bays with the dominant tillandsia species being T. bulbosa and T. disticha. Tillandsia dyeriana, T circinnatoides and T. usneoides may also often be observed in the upper canopy.

Rainforest

These generally occur in warm lowland areas, where rainfall is regular and usually remains consistent throughout the year with little seasonal change. The tillandsia species which grow in this habitat are generally soft/thin leaved, tank-type with sparsely trichomed leaves as light requirements are comparatively low and rainfall regular. Most tillandsias tend to be situated within the mid to upper canopy to maximise light capture.

An additional adaptation by some has allowed them to colonise even the lower parts of the canopy where low light availability exists, this being discolourous leaves which allow this existence, whereby the upper leaf surface (adaxial) remains green but the lower leaf surface (abaxial) is a deep red colour e.g., some forms of T. wagneriana and T raackii. This is common for many rainforest plants. It works by the reflective properties of the anthocyanins which produce this colouration in the leaf. As light (short wave lengths) pass through the tree canopies, it becomes proportionally enriched in red light by selective absorption of the shorter wave lengths. It reflects unabsorbed red light (called back scattering) back into the green mesophyll (photosynthetic tissue) to maximise photosynthesis.

Montane including Cloud Forest

These occur in mountainous areas and are generally referred to as mid to high montane areas or highlands–approximately 800 m to 3000 m above sea level. The temperature tends to be cooler, with high humidity and available moisture. The Andes provide some of the greatest mountain ranges supporting vast cloud forest and abundance of tillandsia species. Mexico and Costa Rica also support some very diverse tillandsia populations within their deciduous and pine forest highlands.

Included within the highlands are the Guiana Highlands in southern Venezuela, northern Brazil and south-east Columbia. These experience extreme conditions which are heavily leached by the high rainfall with little soil and vegetation. Ten (10) species of tillandsia occur in and around the highlands, most on the lower mountains or foothills with one only, namely T. turneri, actually growing on the summit of Mount Roraima.

Desert (Coastal Desert and Semi-Desert)

These occur in areas with low precipitation, being less than 300 mm and down to 10 mm per year and with little vegetation. Some shrubbery and small trees exist in selected areas where the upper range of rainfall exists. Survival in these areas is due to their ability to capture and utilise atmospheric moisture.

Some coastal areas are very rocky, but quickly become predominantly sandy, undulating mounds. Ecuador and Peru provide some of the greatest coastal deserts where T. purpurea exists as a monoculture in pure sand. Not even cactus can survive in some of these areas. Similarly, T. paleacea sweeps through the Peruvian desert like waves of carpet as clumps cause small sand dunes to form. They always grow in long strands with their growing tips orientated towards the sea as they die off from the landward side. They do this to survive by capturing any available atmospheric moisture. For an extended period of time it never rains, which is referred to as the dry season. The only available moisture is from the winter and spring fogs moving up from Chile to southern parts of Peru which envelop the desert coast. The fog does not reach certain places, which creates a patchy distribution. Tillandsias start to disappear the further you move away from the sea as the fog thins. They only exist in areas regularly swept by sea breezes and are never found in areas sheltered from them.

Tillandsia species growing in these extreme deserts produce few flowers and seed due to such harsh conditions. They primarily reproduce vegetatively, whereby individuals detach themselves readily and are transported by wind. They then re-establish in new areas if conditions allow.

Beyond these sandy deserts in Peru are the semi deserts with almost a total lack of rain–only 10-50 mm annually. T. tectorum tends to be the dominant plant in the valleys where only the wind currents (sea fog), particularly in winter, spreads far up into the valleys. Sufficient humidity is carried by these winds for the tillandsias to survive due to their large trichomes - the wind in the valleys blows every day towards noon and brings in enough humid air.

Semi deserts also exist in Mexico where species such as T. xerographica grow. Short trees to 6 m dominate the area which hosts these plants, including many rocky boulders. They experience a long dry season that may stretch over nine months or more. To survive these extreme dry periods they rely upon the morning dew as produced from the cool nights experienced.

In other semi-desert areas, as found in southern Bolivia and adjacent Argentina and Colombia to eastern Brazil, sclerophyllous vegetation grows and also experiences a long dry season that may stretch for many months. Irregular torrential rain falls during the cooler season; however, during the extended dry season they primarily rely on humidity. In these harsh environments some tillandsia species will never flower when just one plant. Several offsets have to be produced whereby an inflorescence will only form when a clump is produced - being many years old. This is due to the nutrient stress imposed on them by an infertile habitat and sufficient nutrient reserves built up within the plant as achieved by the clump to support a flower.

References Cited

Leme E & Marigo L (1993) Bromeliads in the Brazilian Wilderness. Marigo Comunicacao Visual, Rio de Janeiro.

McPherson S (2008) Lost Worlds of the Guiana Highlands. Redfern Natural History Productions, England.

Oliva-Esteve F (2002) Bromeliaceae III. Oliva-Esteve Editions, Venezuela.

Rauh W (1979) Bromeliads For Home, Garden and Greenhouse. Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset.

Rauh W (1966) The Bromeliads of the Peruvian Andes. The Bromeliad Society Bulletin 16 (2).

McWilliams E L (1968) Natural & Cultivated Bromeliads in South-eastern Brazil. The Bromeliad Society Bulletin 15 (6).

Benzing D H (1970) The Origin and Significance of Certain Growth Forms in the Bromeliaceae. The Bromeliad Society Bulletin 20 (2).

Oeser R (1971) Tillandsias – Their Great Adaptability. The Bromeliad Society Bulletin 21 (3).

Benzing D H (1980) The Biology of the Bromeliads. Mad River Press, California.

Ehlers R (2009) Die Bromelie. The Green-Blooming Small, Grey Tillandsias from Mexico. Deutsche Bromelien-Gesellschaft, Markkleeberg.

Burt-Utley K & Utley J F (1980) Phytogeography, Physiological Ecology and the Costa Rican Genera of Bromeliaceae. Journal of the Bromeliad Society 35 (3), 99.

Richter W (1957) Bromeliads – Geographical Distribution. The Bromeliad Society Bulletin 8 (2).

Reitz P R (1959) A Diagram of Bromeliad Habits. The Bromeliad Society Bulletin 9 (5).

TILLANDSIA USNEOIDES

By Derek Butcher, South Australia

All of us grow this plant with varying forms of success. Some of us even grow the 6, or is it 7, or 8 different forms that are around. It is hard to nail down some of these forms because they seem to change according to season and where you have them hanging around.

Experiments in the 1930s showed that the plant grows faster when the strands are horizontal but they do not stay horizontal for long! In Adelaide we have found that our dry conditions are not conducive to continual fast growth, with main growth being when and if Autumn rains come, and Spring. The Spring growth is to prepare itself for flowering around Christmas time. Surely you have all smelt its fragrance. If you obtain just one strand, your chances of success are minimal. You need a clump which will retain some moisture for a longer period by staying close! But then again it needs to hang to dry out!

Just how do you hang it? It will hang on anything and many things have been tried.

About 30 years ago some bright spark thought up pine cones because as they open up there are small ‘pegs’ to hang your T. usneoides on! But then we found that T. usneoides was even slower using this method and we put it down to growth inhibitors used by pine trees to hinder plant growth other than pine nuts! Sneaky but true! So we started to tell everybody in South Australia, “Keep away from pine cones, ‘cos you’ll do better using something else!” I notice the Brom groups in northern New South Wales are advocating the use of pine cones but this may be because T. usneoides grows too fast there because of their rainfall: it needs to be slowed down!

Anyone who has grown T. usneoides for some time with some success will know that any part of the plant that is at the centre of the bundle will be dead. This indicates that the bundle is too fat but it needs to be fat to retain moisture, at least here. A dilemma! I have gone part way to success by making a short cylinder of plastic netting—the squares are about 2.5 cm. I stuff the strands into the holes, hang the contraption up and eventually you get a regular sort of shape! Growth is mainly at the bottom and the weight pulls down the plant away from the plastic squares. So you pull off the bottom strands and place them on top! I think this is called recycling.

Be careful where you grow your T. usneoides because foreign birds like blackbirds will pinch it for nesting material. Do not go to extreme precautions like one of our members who kicked the birds out of their cage and replaced them with T. usneoides! Native birds seem more co-operative because we have had a honeyeater make a suspended nest in a clump. Photos are on fcbs.org if you do not believe me!

USING TILLANDSIAS AS A SCREEN

By Bob Reilly, Queensland

In southern coastal Queensland, Spanish Moss and Tillandsia mallemontii can be used to form screens in the garden. In both cases, select locations which, at least, receive shade in the afternoon. This is especially important in summer. Good air movement, such as that occurring in “breezeways” or locations with a north-easterly aspect, is also important. This is especially true for T. mallemontii. However, avoid locations which are exposed to cold, dry winds.

Build a framework for the screen out of wood or galvanised pipes. A wide variety of material can be used to form the lattice from which the tillandsias are hung. Examples include: timber lattice panels (but not those which have been treated with a timber preservative), plastic garden mesh, weldmesh fencing panels, and galvanised wire netting (but avoid rusty wire).

For Spanish Moss, hang strands along the mesh. Use strands which are two or three plants “thick”, and hang down the full length of the framework. Leave a gap of 2 cm to 5 cm between each strand.

Tie two to five plants of T. mallemontii to the lattice. Use plastic covered wire or strips of nylon pantyhose to do this job. Each cluster of plants should be separated at intervals of about 5 cm horizontally, and 7 cm to 10 cm vertically. (This job can be quite time-consuming. However, you can do it when you are watching television or doing similar activities. In this regard, it is a bit like knitting.)

Water the tillandsia “walls” once a week in winter and twice weekly in summer. Use liquid fertiliser every fortnight. The tillandsias will form an effective screen within one year. They need “renovation” every three years, as they “thicken up” over that period. In turn, this results in plants in the centre of the clumps which have formed not receiving sufficient light, air movement, water or nutrients.

Front: Val, Dulcie, Nina |